Timeline:

1969 – Les puits errants

1970 – Aya bombé drama

1971 – Coumbite

1972 – Mémoires d’un balai

1973 – La parole des grands fonds

1973 – Spectacle with the group Les Batuki

1975 – Quel mort tua l’empereur ?

1977 – Les chants de Mélanie

1978 – Telcide et Duréna

This spectacle was presented in 1969 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music as a launch for the vinyl record Pierrot le Noir and was staged by Hervé Denis. It is a collection of poems by three Haitian exiled writers living in Montreal: Jean-Richard Laforest, Emile Ollivier and Anthony Phelps. It is a montage inspired by these poems as well as extracts of work by Kateb Yacine and Aimé Césaire.

Play in two parts presented at Columbia University in 1970 as well as on other stages in New York City. Staged by Hervé Denis.

This show was conceived as a new vision for a popular theater drawing inspiration in the people, and denouncing the oppression of the system; a theater expression which aims to be complete, integrating dance, music and songs as well as aspects of Haitian folklore; and which seeks to spur a reflection on the contradictions inherent in Haitian society.

The first part consists of a montage of texts by Frantz Fanon, Kateb Yacine, Bertold Bretch, and Aimé Césaire, set against a stage decorated with African mask replicas.

The second part of the spectacle is staged around a dramatic poem by Georges Castera in creole: “Tambou Ti bout la Bout,” pulsing with drum music – a reaction of the people against oppression, as seen by an exile imagining an invasion of the country from abroad.

Coumbite is a form of collective fieldwork in the Haitian countryside in which the participants improvise songs.

Presented in 1971 at New York University, Coumbite is a montage of songs and skits all denouncing the dictatorship in Haiti. Staged by Hervé Denis assisted by Jacky Charlier.

The first skit opens with popular songs against oppression.

A storyteller tries to find a new way to welcome the public. He is interrupted by the arrival of Uncle Sam and his dog: a Tonton Macoute.

The storyteller continues his commentary. He is interrupted again by a religious procession. His voice drowns the whimpering lamentations of the worshipers. The story teller and the worshipers band together in a chant against oppression: ‘Chwal la galonen”.

Humorous skit on the daily life of Haitian communities abroad.

Western Union Telegram: Duvalier is dead- American marines supporting son in power. Everyone cracks up laughing, bitterly.

Haiti’s plight told on the carcass of a decaying sailboat: “Back home, every night the moon slakes it thirst for blood at Fort Dimanche…”

Remembrance of the streets of Port-au-Prince: “Ri Lanteman, Ri Kapwa, Lali, Ri Pave, Gran Ri…”

“The Holy Ghost”: a young man is killed by a Tonton-Macoute priest inside a church.

“Vwa n ap donin” – “We raise our voices”: a chant to remember and celebrate all those who died for the liberation of Man.

“Nou pap domi bliye” – “We will never forget”: Hymn to the memory of the Latin American Freedom Fighters.

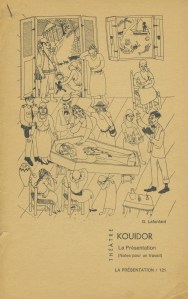

Mémoires d’un Balai is a play in 10 acts written by Syto Cavé, staged by Hervé Denis and presented in 1972 at Columbia University, at the Festival of the Nations at the Sorbonne (Paris, France) and in 1973 at the Cultural Festival of Fort-de-France, Martinique. The central theme of this play is the carnival, experienced not as a celebration but as an itch, a barrier and a questioning. What hides behind the masks? Other masks?

A King, a Queen, their subjects: an ambulatory realm which affirms and exhausts itself, a dream… a dream reeking of the smell of garbage bins.

There is also this persistent grime which resists all attempts from the sweeper’s broom… Port-au-Prince: a place rustling with interferences… Throughout the play the atmosphere is surreal.

The stage: an alley in a slum of Port-au-Prince where a group of unemployed people meet every day to discuss their situation. A sweeper observes them and comments on their conversation. He is interrupted by Vierge who tells him the story of an unfortunate star.

The group continues their debate until a Tonton Macoute walks in and summons them to participate in a nearby carnival. He chooses a King and distributes clothing to be worn at the carnival. The sweeper keeps commenting on the scene and Vierge starts telling him the story of a butterfly singed by a lamp.

The carnival starts: music, dance. The King addresses the crowd as well as his subjects and tells them how the carnival will help them let off steam from their frustrations, however he is mindful of the Tonton Macoute watching him.

The sweeper is increasingly feeling powerless with his broom in front of the Tonton Macoute and tries to retell, from his own perspective, the story of the kingdom.

The King orders the end of the carnival: “Let’s take off our masks!”

A meat patty peddler arrives and the Tonton Macoute offers food to everybody. But when the patty peddler demands to be paid, he pulls out his gun and everyone flees, except the Queen who is taken as hostage by the Macoute.

While the Queen is forced to endure the advances of the Tonton Macoute, the King takes out the suppressed anger he cannot let out on the Tonton Macoute on his subjects.

The sweeper is really stressed at this point: he sees his phantasmagorical world (his imaginary relationship with Vierge) collapse in front of reality: he is attacked and kicked by two of the girls of the group who refuse the flowers he gave them which they crush under their feet.

Written by Syto Cavé and staged by Jacky Charlier, La Parole des Grands Fonds is a play in 7 acts on the dynamics between the city and the rural worlds of Haïti. It is presented in 1973 at the First Cultural Festival of Fort de France, Martinique.

Opening: a group of four women in frilly gowns with sun hats and fans are saluting the public and setting the stage; two gentlemen in formal suits and black tie; an old man in faded formal suit and a young man casually dressed.

A country person walks in and announces himself with comments about what he sees in town. The group starts sniggering and commenting on his appearance and every gesture he makes. The conversation takes sexual overtones and the dandy is rapidly distressed and overcome by the innuendos.

A chorus sets the backdrop for a dialogue between a girl and an old man describing vividly the vehicles crossing the village.

A banker gives a speech on capital, arguing in comical terms that it needs to be friendly to the people.

A judge presents a tortuous argument for building more jails, a reference to the infamous Fort-Dimanche.

A group of women wearing black glasses reads a list of press releases – parroting the government.

A funeral vigil led by a Pe Savan (self-proclaimed priest) accompanied by a chorus praising the qualities of the deceased.

Written by Jacky Charlier and Syto Cavé, this play was presented in 1975 at the Second Cultural Festival of Fort de France, Martinique.

The assassination of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Emperor of Haiti, one of the heroes of Haïti’s independence, remains to this day a vivid part of the Haitian psyche and folklore. He was immortalized by being consecrated a Vodou god, and the subject of many folk songs and tales.

The central characters are the Emperor and Défilée, the madwoman who collected his remains and had them buried.

*This is a Haitian creole expression which can be loosely translated as : “Which bad spirit killed the emperor?”

LES CHANTS DE MÉLANIE

(The Songs of Melanie)

1977

(Synopsis to follow.)

TELCIDE ET DURÉNA

(Telcide and Duréna)

1978

Written by Syto Cavé with text by Régine Charlier.

Two elderly women of 80-90 years old. They are from the countryside.

They have been working as domestics for liberal bourgeois and for black bourgeois. They have crossed the spectrum of Haitian society, and find themselves in the same situation. Nothing changed. Even Stevens!

In this play, in spite of their old age they go on making a living and moving along. Their words are rhythmic. All their conversations follow a rhythmic pulsion. Around them revolve other characters such as the woman representing a dreamer whose words carry the Congo rhythm even though one cannot hear the rhythm per se; the mad woman’s words come out as a Yanvalou rhythm and the violent man speaks with the Petro rhythm; even though one cannot hear the specific rhythms, their words are chanted on the Petro rhythm, the Congo rhythm.

“We were doing rap without knowing it”.